The Hoodlum

Those Were The Days

The Early Years

Origins

Pioneers

The Sidesaddle Club

Grandpa Memoir

Willkommen

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

Almost any list of Americans-the roster of a baseball team, a class

attendance sheet, a telephone book-includes a large number of German

names. Some are not obviously German (Houser, Newman, or Berger), and

often even the individual who bears the name is not certain of its

origin. Americans of most ethnic backgrounds have intermarried to such

an extent that about two-thirds now claim multiple ancestry, and German

Americans are no exception.

In 1986, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, for the first time in more

than 300 years the leading ancestral background of America's residents

was no longer British, but German. Roughly 44 million Americans, or 18

percent of the populace, claimed sole or partial German heritage, a few

hundred thousand more than claimed British descent.

Because the German-American population is so large, it is hard to

generalize about it. Americans of German descent spring up in virtually

every occupation, live in every state, and hold a spectrum of political

and religious beliefs. In short, they typify America. Indeed, the vast

majorities are Americans of long standing; only 4 percent of today's 44

million German Americans were born in Germany.

The term German American encompasses a number of peoples. Before 1871,

Germany was not a nation, but a collection of dozens of small state

kingdoms, and principalities, each with its own ruler, customs, and

regional dialect. Over seven centuries speckled with migrations, wars,

and religious conflict, these lands covered much of north central

Europe, from the North Sea to the Nieman River near Kaunas, Lithuania.

So speakers of German came from what are now parts of Denmark, the

Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary,

Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Soviet Union. Immigration officials in

the New World sometimes listed people as Germans although Germany was

not their land of origin. If the annals of history have sometimes lumped

diverse people under one umbrella term-German-it is a simplification we

must now acknowledge, if not embrace.

PRESENT FROM THE INCEPTION

Beginning in 1683, Germans formed the first substantial group of

non-English-speaking immigrants to settle in America. By the outbreak of

the revolutionary war in 1776, their numbers had reached 225,000. More

so than most other ethnic groups, who arrived in the 19th and 20th

centuries, German immigrants have had more time to adapt, intermarry,

and to disperse throughout the nation.

The revolutionary war and subsequent conflicts in both America and

Europe slowed immigration, but Germans continued to sail to these

shores. Beginning in the late 1830s, they came to America in record

numbers, surpassed only by the Irish. They thereby retained their status

as the largest non-English-speaking group. In 1882 alone, a quarter of a

million Germans arrived in the United States.

The Germans who arrived during this later period (1816-90) differed in

several ways from those who had arrived earlier. Whereas most German

immigrants of the 18th century came from the Palatine or Württemberg,

states along the Rhine River in the southern and western regions of the

German lands, those in the second wave of immigration came mainly from

the north and east-Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony.

Those who came before 1871, the year Germany was unified, tended to be

loyal to their particular state or locality, rather than to Germany as a

whole. Thus, Germans were not inclined to bond as one identifiable group

in the United States. Albert, John and Mathilda Caroline Dorothy Poppe

Severt immigrated in 1875, four years after Germany had become a unified

state. Even today, a recent German immigrant may refer to him- or

herself as a Saxon, Bavarian, or Berliner.

German immigrants came not only from all parts of Germany but also from

all walks of life and for many different reasons. In the 18th century,

religious persecution prompted many emigrants to cross the Atlantic,

often in groups-families, parishes, and sometimes-entire communities

traveled together. In the 19th century, political oppression at home

encouraged many idealistic and utopian plans for a free colony of

Germans in the United States. These new immigrants were often better

educated and more politically minded than their predecessors.

Still, the overwhelming majority of immigrants came in search of better

economic opportunities. In the years before the Civil War, German

newcomers tended to be independent craftsmen or farmers and their

families, who could afford the cost of passage and could meet the

demands of the developing and still largely agricultural countries of

the United States and Canada. After the Civil War, the rapid growth of

industry in America and the advent of the more convenient and affordable

steamship enticed German day laborers who had no families and no special

skills.

The 20th century created yet another sort of immigrant, the wartime

refugee, especially just before and during World War II. The total

number of refugees was comparatively small, but they made an impact in

the sciences, business, and the arts. Many were Jews, who were joined by

Catholics, Protestants, and others who professed no religion, in fleeing

Hitler's regime of 1933-45.

Events in America served to divide further a population that had already

been broken up along religious, class, and territorial lines. Because

they arrived during different periods and at a variety of ports, German

immigrants settled all over the United States. Many gravitated to

cities, where they blended into the general population more quickly than

they would have in the countryside. Though German Americans are now

dispersed across the continent, their history and culture figure most

evidently in a handful of strongholds: St. Louis, Cincinnati, Milwaukee,

Philadelphia, and parts of the Middle Atlantic states and the upper

Midwest. (The fabled Pennsylvania Dutch are not Dutch but Germans, whose

name for themselves, Deutsche, was misunderstood by their Yankee

neighbors.) In those locales they have long been the dominant group,

though fierce anti-German sentiment aroused by World War I effectively

discouraged German cohesiveness in all but the sturdiest of their

communities.

The sheer number of German immigrants, their 300 years of immigration,

their diversity in class, religion, and occupation, and their

experiences in the United States have all played a role in their rapid

assimilation and subsequent lack of visibility. Yet these same factors

have also allowed them to influence American culture in a multitude of

ways.

HIGH AND LOW GERMAN

The German dialect was divided into High German in the south and Low

German in the north. High German refers to the low coastal plain in the

north. Boats go down the Rhine in a northwesterly direction from Basel

to Rotterdam and down the Elbe in a northwesterly direction from Dresen

to Hamburg. Because maps often hang on walls with north at the top, we

say "up north" and "down south," just as the Germans say "up in

Schleswig" and "down in Bavaria" (unten in Bayern), so it is sometimes

hard to remember that High Germany is in the south and Low Germany is in

the north. The High German sound shift, which altered most consonants,

began soon after the Alemanni and Bavarians reached the Alps following

the collapse of the Roman Empire.

The High German sound shift gradually spread northward into central

Germany and affected standard German, while the North Germans clung to

the unshifted consonants of the other Germanic languages such as Dutch

and English. Thus the German dialects were divided into High German in

the south and Low German in the north.

SETTLING THE NEW NATION

The American Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars in Europe (1801-15), and

the War of 1812 all discouraged emigration to the New World. Instead,

the first 40 years of the American republic were years of assimilation

rather than expansion for the German-American population. Still,

immigrants trickled in. In 1804, a group of separatists from Württemberg

founded Harmony, Pennsylvania. Like many of their 18th-century

forerunners, these settlers-known as Rappists after their leader, George

Rapp-sought to live by the Scriptures. They practiced celibacy, and

residents signed over all personal wealth to create their "Community of

Goods." In 1814, the Rappists moved to Indiana, where they established

New Harmony on 30,000 acres, but "to avoid malaria and bad neighbors"

they headed back to Pennsylvania 1O years later. Their final home was

Economy, on the Ohio River, 20 miles north of Pittsburgh. Here, finally,

they found prosperity-oil wells, coal mines, and numerous factories

sprang up by the 1820s.

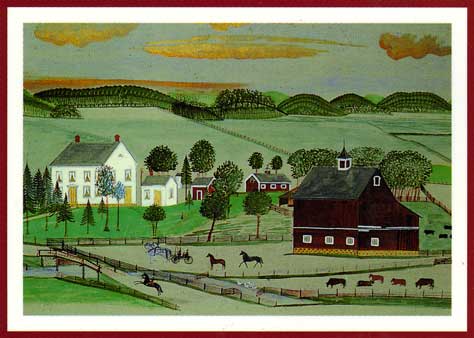

Wisconsin Farm Scene by Paul A. Seifert (1840-1921), watercolor, ca. 1880

Other American communities founded by religious Germans and run-often

very successfully on the principle of common ownership of property

cropped up later: Zoar, Ohio, in 1819; Bethel, Missouri, in 1844;

Aurora, Oregon, and Amana, Iowa, in 1856. But by and large, the emigrant

leaving his home for religious reasons was a rarity in the I9th century.

A Württemberg government survey found that among those leaving the state

in 1817, almost 90 percent left "to overcome famine, shrinking means,

and unfavorable prospects." This was reflected in the makeup of the

emigrant groups: while in the 18th century entire communities left

Germany together, in the 19th century almost all emigrants traveled as

individuals or in small family groups, Not all chose America; two-thirds

of the emigrants set out for Austria-Hungary or for Russia. During the

1820s, only 6,000 to 8,000 Germans reached the United States.

By the end of the decade, several factor were encouraging German

emigration. Overpopulation and a shortage of cash for trade, combined

with the traditional practice of Realteilungsbrecht-the division of the

family farm among many descendants-created enormous economic pressures.

Many families had coped with shrinking farmlands by taking up

handicrafts such as Clockmaking or weaving, but after the end of the

Napoleonic Wars Germany was flooded with cheap factory made English

goods that brought disaster to German family industries. The appearance

of Gottfried Duden's book Report on a Journey to the Western States of

North America in 1829, thus was timely. His account of life on a small

farm in Missouri sounded idyllic to those who saw their way of life fast

slipping away from them.

NEXT STOP: MISSOURI

With a population of about 70,000, Missouri became a state in 1821.

Duden purchased 270 acres of land in present-day Warren County,

Missouri, in 1824 and he was soon convinced that planned farm

communities of Germans were feasible. "No plan in this age," he wrote,

"can promise more for the individual or group."

The careful advice he gave was less compelling than his descriptions of

daily life. Duden spent the hour before breakfast "shooting partridges,

pigeons, or squirrels, and also turkeys," and the rest of the day

unfolded in a leisurely fashion: he read, strolled in his garden,

visited neighbors, and "delight[ed] in the beauties of nature." His

assurances that the educated man could make a go of it on the American

frontier fed the imaginations of many young liberals in Germany,

intellectuals disgusted with the reactionary policies the German states

adopted after the Napoleonic Wars.

The Giessen Emigration Society, founded in 1833, was the first of many

such organized emigration movements to try to profit by the

disenchantment in the old country. Their pamphlets, widely distributed

in southwest Germany, urged readers to join them and help found "a free

German state, a rejuvenated Germany in North America." The Giessener

Gesellschaft society developed plans to concentrate Germans in a

territory which could eventually be admitted to the Union as a German

State. During the decades that followed, three states came under

consideration for such ambitious dreams - Missouri, Texas, and

Wisconsin. That state was never realized, as a group of about 500

emigrants under the society's auspices disbanded upon reaching St.

Louis.

Many of the Giesseners were dubbed "Latin Farmers" because of their

classical education. They soon discovered that pioneer farming was not

as leisurely as Duden had described. Karl Buchele, in an 1855,

summarized their predicament: "The German philosopher who ... has here

become a farmer, finds that the American axe is more difficult to wield

than the Pen, and that the plow and the manure-fork are very

matter-of-fact and stupid tools." Another disgruntled immigrant labeled

Duden a Lugenhund (lying dog), and Duden felt compelled to retract some

of his own advice in an 1837 sequel to his 1829 book.

In the time between the two books, however, more than 50,000 Germans

emigrated, many of them at Duden's suggestion. Many came from areas of

Germany Hannover and Oldenburg, for example-that had previously lost few

citizens. The Latin Farmers formed the vanguard of German settlement in

Missouri, and the ' quickly spread into southern Illinois. In spite of

all gloomy predictions, they came to be an important local influence,

establishing libraries, schools, and newspapers.

A colonization attempt inspired by the Giessener Society later in the

decade proved even more successful In 1837, the German Philadelphia

Settlement Society bought about 12,000 acres in Gasconade County, across

the river from Duden's land, then dispatched an advance party of 17 to

spend the winter on the property. This group was joined by a steadily

increasing flow of members from back east, and by 1839, when it was

incorporated, Hermann, Missouri, boasted 450 inhabitants, 90 houses, 5

stores, 2 inns, and a post office. The society dissolved in 1840, but

Hermann and the surrounding district gave rise to a prosperous fruit

growing and wine-producing industry. In this "Little Germany," wrote a

visitor, "one forgets that one is not actually in Germany itself"

THE TAMING OF TEXAS

As German immigration accelerated in the 1840s (tripling from the

125,000 arrivals of the previous decade), the desire to bolster cultural

and economic ties with the New World became popular in Germany. Yet

colonization proved no easier than it had been in the 1830s. All over

Germany, local societies to aid the emigrant sprang up, but without a

unified central government the region could not promote the concerted

settlement that such countries as France and England managed.

Independent attempts-like that of the Giessener Society-tended instead

to open up areas for subsequent immigrants who acted on their own.

Such was the case in Texas. An independent republic from 1836 to 1845,

Texas was a likelier prospect than Midwestern states for colonization

schemes. The Germania Society of New York, founded in 1838, chose Texas

because "the plan of founding a pure German state in the midst of the

American Union would arouse the opposition of the American people." An

outbreak of fever among settlers in Galveston in 1838, however, forced

the society to abort its plans.

News of Texas had reached the northeastern states of Germany by way of a

letter sent in 1832 by immigrant Friedrich Ernst to a friend in

Oldenburg praising the land and life in Texas. Published first in an

Oldenburg newspaper and then in a book on Texas, the letter induced the

first wave of German immigrants-mostly from the states of Oldenburg,

Westphalia, and Holstein-to emigrate to Texas. One man whose imagination

was captured by Ernst's letter wrote that it depicted a beautiful

landscape "with enchanting scenery and delightful climate similar to

that of Italy" and "the most fruitful soil and republican government."

These attractions enticed settlers much like those who had responded to

Gottfried Duden's descriptions of Missouri. Like the Latin Farmers, some

of these newcomers were disillusioned upon their arrival. One immigrant,

Rosa von Roeder Kleberg, wrote, "My brothers had pictured pioneer life

as one of hunting and fishing, of freedom from the restraints of

Prussian society; and it was hard for them to settle down to the

drudgery and toil of splitting rails and cultivating the field, work

which was entirely new to them."

Between 1831 and Ernst's arrival, Germans continued to go to Texas, but

compared to the influx of Germans into Missouri, Texan settlement was

slight. In 1836, the total number of Germans barely exceeded 200. Texas

seemed too remote to most immigrants. It was also vulnerable to attack

by Comanche Indians from the west.

Nevertheless, in 1843 the republic was chosen for a colonization project

known as the Adelsverein (nobles club). Composed of 24 rulers and

nobles, the Germania Society aimed, "out of purely philanthropical

reasons," to "devote itself to the support and direction of German

emigration to Texas." No doubt Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels, the

commissioner general of the project, envisioned other, more glorious

objectives when he wrote tight money spurred tens of that "the eyes of

all Europe are fixed on us and our undertaking."

The society's prospectus detailed the terms of new Fatherland beyond the

Seas." For the equivalent of $120, a person received free passage and 40

acres in west-central Texas. From December 1844 (when the first 3

shiploads of immigrants landed at Carlshafen, later renamed Indianola)

to 1847 (when the society went bankrupt), more than 7,000 Germans were

transported to Texas under the auspices of the Adelsverein. Prince Carl

von Solms-Braunfels proved to be an incompetent leader, preoccupied with

decorum rather than the nuts and bolts of founding a town. He built a

stockade, called Sophienburg in honor of his lady, and manned it with a

courtly company of soldiers. He did, however, with 180 subscribers,

found the town of New Braunfels in 1845. This settlement, wrote one

American visitor, was an eventual success, "in spite of the Prince, who

appears to have been an amiable fool, aping, among the log-cabins, the

nonsense of medieval courts."

In 1845, the prince was replaced as commissioner general, but adversity

dogged the immigrants. Comanches threatened attack; the United States

had begun its war with Mexico over the annexation of Texas; and the

society was debt ridden. One thousand of the settlers died in squalid

camps on the coast.

Those who survived were encouraged to spread out over new land northwest

of New Braunfels. Particularly notable was the founding of

Fredericksburg in April 1846. Named in honor of Prince Frederick of

Prussia, it was the first white settlement in the northwest hill country

of Texas, and by 1850 it had a population of nearly 2,000. An

enthusiastic inhabitant wrote to a friend:

If you work only half as much as in Germany, you can live without

troubles. In every sense of the word, we are free. The Indians do us no

harm; on the contrary, they bring us meat and horses to buy. We still

live so remote from other people that we are lonely, but we have dances,

churches, and schools.

Such letters spurred further emigration to Texas, unmanaged by any

colonization society. Estimates of the number of Germans who settled in

Texas before the Civil War reach as high as 30,000. In 1857, a Orleans

editor wrote that every ship leaving from that port for Galveston was

"crowded with Germans of some wealth ... going to select a future home.

" The area of heaviest German concentration stretched from Galveston

northwest to Austin, New Braunfels, Fredericksburg.

In Texas, as in Missouri (and later, Wisconsin), the idea of a "new

Germany" was never realized. The idea did, however, encourage settlement

in rural, undeveloped areas of the country. And a large proportion of

Germans arriving in the United States in the period from 1830 to 1860

looked as well to a different kind of destination for a new life: the

growing cities of the Midwest.

GROWING WITH THE CITIES

There was a variety of reasons for heavy German settlement in Midwestern

cities during the 19th century. For the lower-middle-class immigrants of

the earlier period (1830-45), Cincinnati, Ohio; St. Louis, Missouri; and

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, offered the skilled craftsmen many opportunities

for employment in agriculturally related occupations (brewing, tanning,

and milling). To farmers, cities offered a stopover, a place to earn

enough money to buy land in the surrounding countryside. St. Louis also

became the home for those the cultured Germans who had tried, and then

abandoned, the difficult life of the pioneer farmer. After 1845, with

the incoming German population composed more and more of people with

little means and few skills, laborers were drawn to the Midwest by the

promise of plentiful employment in fields such as construction and

transportation. One writer gave this advice: "Lose no time ... in

working your way out of New York and directing your steps westward,

where labor is plentiful and sure to meet with its reward."

Travel routes, westward from New York or north from New Orleans, played

a major role in determining the destination of may 19th-centry

immigrants. Natural and man-made waterways were the "highways" of the

1830s and 1840s. The Erie Canal, opened in October 1825, was especially

important, linking the Atlantic coast with the region beyond the

Allegheny Mountains. Arriving in New York (the busiest port of the

mid-19th century), an immigrant could take a steamboat up the Hudson

River to Albany; a week's trip from Albany on the Erie Canal landed him

in Buffalo. From Buffalo, the Great Lakes provided access to Wisconsin,

Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Minnesota. The advent of the

railroads made travel much easier-by 1851, an immigrant with some money

to spare could cover the distance from New York to Lake Erie by train.

Populations reflected this advance. Chicago in 1845 was eight percent

German; by 1860, when it had become the hub of the flourishing rail

system, Germans accounted for one-quarter of the city's total

inhabitants.

Chicago filched its status as the center of the Midwest from Cincinnati.

Situated at the point where the Great and Little Miami rivers flow into

the Ohio, Cincinnati was the boomtown of the 1830s, the era of the

waterways. Germans contributed substantially to its growth: By 1841, 28

percent of the total population was German; 10 years earlier the figure

was only 5 percent, By 1850, when Cincinnati was known as the "Queen

City of the West," the German community (including those born in

America) made up half its population.

From 1847 to 1855, a period of especially high European immigration

because of poor harvests in the Old World, Germans flocked to Wisconsin.

A state bureau of immigration, railroad companies, and eager immigrants

themselves encouraged settlement in the new state, which entered the

Union in 1848. One German-language newspaper sold stationery preprinted

with a "brief but true" description of Wisconsin. Milwaukee, settled in

1836 where the Milwaukee River flows into Lake Michigan, attracted many

of the newcomers. More than 8,000 Germans arrived there during the

1850s, and in 1860, Germans accounted for 16,000 out of a total

population of 45,000.

Unlike the Irish, who also formed a substantial immigrant population in

Milwaukee, Germans tended to flock together in their own neighborhoods.

Likewise, in Cincinnati, the focus of the German community was an area

known as "Over-the-Rhine," across the canal from the main part of town.

St. Louis, however (where from 1830 to 1850 the population exploded from

7,000 to 77,860), did not boast an exclusively German neighborhood. Its

German population-22,340 in 1850, and more 50,000 just 10 years

later-was spread throughout the city's 28 districts.

Jews also figured largely in the migration from Germany to the United

States in these years. Between 1840 and 1880 the Jewish-American

population grew from 15,000 to 250,000 persons, most of them Germans.

Like their Christian contemporaries, they took their skills and culture

primarily to Midwestern cities, though the Jews tended to be merchants

rather than artisans or laborers. A handful became highly successful

owners of department stores; others, mostly in New York, built

substantial houses of banking and finance, such as the Lehman, Kuhn, and

Loeb families. Immigrant Levi Strauss, for instance, started a dry-goods

store that became the blue jeans empire of today. The seeds of Reform

Judaism, a modernization of some traditional Jewish practices and

beliefs that is now the largest of Judaism's three main branches, also

came from Germany with the immigrants and got its real start in America,

led by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise in Cincinnati. The German Jews settled in

tightly knit communities to better practice their faith-and because they

were barred from many neighborhoods.

Differences in neighborhood arrangements from city to city raise a

question about how German Christians or Jews and native-born Americans

got along. Did the l9th-century German immigrants band together more

than any group at any time, as one historian, John Hawgood, claimed? Or

did they move into the mainstream of American life willingly and

rapidly?

SETTLING IN, FITTING IN

The following comments, made by a visitor to a 19th Midwestern German

community, seem to support Hawgood's theory:

Life in this settlement is only very slightly modified by the influence

of the American environment. Different in language and customs, the

Germans isolate themselves perhaps too much from the earlier settlers

and live a life of their own, entirely shut off.

Although this observer was writing about a relatively secluded rural

settlement in southern Illinois, urban life did not always foster rapid

assimilation into an American way of life either. More than half a

million people emigrated from Germany between 1852 and 1854 alone (many

of them from areas in northern and eastern Germany previously unaffected

by emigration). Sometimes a German immigrant felt a strong pressure to,

in the words of one immigrant writer, "transform himself into a complete

Yankee." But thanks to their large numbers, most Germans found it easy

to preserve at least some distinctive elements of their culture.

Preservation of the mother tongue was of paramount importance in a

person's battle to preserve ethnic identity. As an example, Albert and

Mathida Poppe Severt were very adamant all their lives that only German

was to be spoken in their home or in their presence. If grandchildren

spoke English, they would be ignored or sent home. For the Otto Severt

boys, this presented a problem when they started school and they didn't

have a good command of English. The Evangelical St. Johns Church in

Arpin, Wisconsin with Otto August Severt being a charter member,

continued to conduct services in German until 1917 with an English

service conducted only twice monthly. The church continued to keep

records in German until 1928. Even in St. Louis, bastion of the

idealistic Germans of the recent immigration, the editors of a prominent

German newspaper, the Anzeiger des Westens, mourned "the laming and

corruption of the German language." A German-language school was

established in St. Louis in 1836, two years before the city's public

school opened. By 1860, there were 38 German schools in the city, most

affiliated with Protestant and Catholic churches (though one was Jewish

and one freethinking, or nonreligious). The very number of German

children in these schools provided so much competition with the 35

public schools that in 1864 the local school board voted to include

German language instruction in the public school curriculum. There was

one earlier exception to the rule of division by language: In 1850, John

Kerler, Jr., stated that "Milwaukee is the only place in which I found

that the Americans concern themselves with learning German, and where

the German language and German ways are bold enough to take a foothold."

Kerler described another attraction of Milwaukee its "inns, beer

cellars, and billiard and bowling alleys, as well as German beer."

Indeed, by 1850 there were 7 German breweries in Milwaukee; a decade

later there were 19, some with taverns or beer gardens where informal

gatherings over German-style lager beer helped young men feel at home.

Whole families also gathered there. In fact, in every major Midwestern

city, beer gardens like the Milwaukee Garden (established in 1850 and

said to accommodate more than 12,000 patrons), took the place of public

parks. Suburban "refreshment gardens" appeared on the outskirts of many

Midwestern towns.

Germans were also known for more formal social arrangements. The

middle-class German immigrant brought to the urban and rural Midwest a

tradition of forming and joining associations. These clubs, or Vereine,

provided members both cultural and social nourishment, including drama,

debate, and sharpshooter clubs. Many grew out of a love of music. The

Missouri Republican observed that "the Germans best among all nations

understand how to make music subservient to social enjoyment."

Gesangvereine, or German singing societies, were especially visible.

Baltimore's Liederkranz, founded in 1836, stated its objective as

"improvement in song and in social discourse through the same." The

singing societies built concert halls, produced operas, and organized

national choral festivals where groups from all over the country

gathered to entertain huge audiences. One of America's greatest musical

families started with Leopold Damrosch, a German immigrant of 1871 who

founded an opera company. His son, Frank, was director of the Juilliard

School of Music in New York City, and another son, Walter, was a

conductor with the Metropolitan Opera Company and the New York Symphony

Orchestra in the early 20th century.

Perhaps most characteristics of the German immigrants were the

Turnvereine, or gymnastic clubs. Founded in Germany by Friedrich Jahn in

1811 as a means of promoting well being through exercise, the clubs'

programs also advocated nationalism and the need to defend the

fatherland against Napoleon. In this sense, early Turnvereine were much

like training camps. In America, "turners" still practiced gymnastics

(the St. Louis School system enlisted the head of a local club to

organize its physical education system), but they also arranged picnics,

parades, and dances, serving a social as well as a sporting purpose.

Some clubs took on the role of all-purpose community house in the 20th

century. The Turnverein in Yorkville, New York City's largest German

district, offered kindergarten classes to any neighborhood child before

closing its doors in 1985. Others limited their offerings: The club in

downtown Milwaukee became a German-style restaurant, its walls decorated

with photographs of past gymnasts.

Churches set up their own brand of Vereine. Particularly common in

Catholic parishes, these organizations ranged from mutual benefit

associations (akin to insurance companies) to women's rosary and fund-

raising societies. In Baltimore, a group called the Sisters of Charity

was responsible for that city's first hospital, established in 1846.

German Jews and Protestants also had their own associations.

THE FORTY-EIGHTERS

A particular boost to the sense of German ethnic identity came with the

forty-eighters, a group of 4,000 to 10,000 Germans who arrived in

America as refugees from the failed political revolutions and

social-reform movements of 1848. On the whole they were liberal,

agnostic, and intellectual, traits that threatened or offended many of

the more established immigrants. But the influence of the forty-eighters

on the cultural and political life of the German-American community was

tremendous, and many worked to unite divergent groups of German

Americans around issues that concerned Palatines and Berliners,

Catholics and Protestants alike.

In the years immediately following their arrival, the forty-eighters

continued to support, from across the ocean, the liberal cause in

Germany. But troubling events in this country increasingly drew their

attention. As early as 1835, antiforeign feelings had led to the

establishment of the Know-Nothing party (so called because members

continually claimed they "knew nothing" of the movement); by the early

1850s (coincidental with high mid-century immigration), the "nativism"

favored by the Know-Nothings was on the rise. Nativists tried-through

petition, legislation, ostracism, and open abuse -to restrict the entry

of immigrants into the United States and to limit the rights of those

who had already arrived.

One German custom especially appalling to native-born Americans was

drinking beer on the Sabbath. Many native-born Americans followed the

English Puritan tradition of refraining from frivolous activities such

as dancing, bowling, and drinking on Sundays. Most German Americans had

no such traditional restrictions on Sabbath behavior, and their Sunday

drinking caused such outrage that movements to restrict or prohibit

liquor consumption arose in several states. Although most German

immigrants agreed that moderation in drinking was a good idea, they

viewed these legal efforts as direct attacks on both their way of life

and their religious freedom. In Wisconsin (which by 1855 was heavily

German), one newspaper lambasted "the Temperance Swindle" for reducing

"all sociability to the condition of a Puritan graveyard." A German

theater owner in St. Louis in 1861 defied a police order to close on

Sunday, whereupon 40 officers arrived to prevent the audience from

entering.

The culture gap had an uglier side. An 1855 riot in Louisville.,

Kentucky, led by the Know-Nothings, was one of the era's more blatant

and violent manifestations of anti-German feeling. Catholics (both

German and Irish) were frequently victims of attacks by nativists, who

wanted a Protestant America. In the years immediately preceding the

Civil War, opponents of slavery were also targets. Many of the more

prominent German Americans, including most of the forty-eighters, spoke

out against slavery, antagonizing slave owners and their supporters.

Most of these activists, moved by the strong anti-slavery stance of

Republicans such as forty-eighter Carl Schurz, joined the Republican

party soon after its founding in 1854. Although the average German

immigrant did not own slaves, the Democratic party retained significant

German-American support because it had formed the primary opposition to

the Know-Nothing party in the past.

In general, German Americans felt more strongly about the preservation

of the Union than about the abolition of slavery. By the time Republican

Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, seven southern

states had already seceded from the Union, and German Americans

(Republicans and Democrats alike) frowned upon this breach of national

unity. After all, it was the search for economic and political stability

that had motivated many of them to emigrate.

In December 1860, pro-Southern soldiers known as Minute Men resolved to

further the cause of secession in the border state of Missouri. But the

next May, federal troops thwarted their plans, capturing the

pro-Southern state militia at Camp Jackson, near St. Louis. Many of the

soldiers who stopped the Minute Men were German volunteers, members of

Turnvereine or of Wide-Awake clubs (German organizations originally

formed to protect Republican speakers at political rallies in Missouri).

The result was that Missouri stayed in the Union, and German-American

soldiers received much of the credit for the political victory.

Thousands of young German Americans-from Pennsylvania to Colorado-fought

in the Civil War. Henry A. Kircher, 19, a first-generation American from

Belleville, Illinois, left a record of his Civil War experiences in his

letters home to his family. He initially joined the 9th Illinois

Infantry but soon left, at least partially in response to ethnic

tensions between Germans and Americans in that regiment. With a few

other Germans from Belleville, he then joined the 12th Missouri

Infantry, a regiment composed primarily of foreigners and led by German

officers with such names as Osterhaus, Schadt, Wangelin, and Ledergreber.

In August 1864, after the Battle at Ringgold Gap (Georgia), Kircher's

right arm and left leg were amputated; Captain Joseph Ledergreber died

from shots through the lungs and spine. In sum, thousands of German

Americans were injured or lost their life in battle. From the time the

Civil War ended in April 1865 to well into the next century, German

Americans pointed to these sacrifices for the Union as proof of their

patriotism. For many, the Civil War would mark a turning point in their

sense of themselves as American citizens.

INDUSTRIALIZATION AND WAR

Two themes characterize German immigration in the decades between the

Civil War and World War I. The first was a great increase in the number

of new arrivals. The 1880s were the peak years of this exodus from the

fatherland: In that decade, 1,445,181 Germans made their way across the

Atlantic, about a quarter of a million of them in 1882 alone.

But a second, countervailing force was at work. In these same years,

emigration from southern and eastern Europe began to climb, so that

Germans fell sharply as a percentage of America's foreign-born

population. Whereas in 1854 Germans accounted for about half of all

foreign-born persons in America, by the 1890s that figure had fallen to

less than one-fifth. Compared to the wave of Italians, Russian Jews,

Scandinavians, Poles, and others, the Germans were in some senses part

of the old America, a cultural presence that harked back to colonial

times. These two facts changed the nature of the Germans' adaptation to

their new homeland.

The source of German immigration was shifting, too. Whereas pre-Civil

War immigrants hailed from the Southwestern agricultural regions along

the Rhine, the later arrivals were more likely to emigrate from the

Hesses or Nassau. These northeastern states were dominated by estate

agriculture, in which land was farmed commercially rather than by

individual families. Consequently, a growing percentage of the emigrants

were day laborers who had worked other people's fields, and who also,

upon arriving in America, found most of the farmland occupied.

CLOSER TO HOME

Marshfield, Wisconsin was an immigrant community, settled predominately

by German-speaking settlers. When war erupted in Europe, not only

President Wilson but many Americans had to stand aside and practice a

policy of neutrality, to keep the political loyalty to their new country

in balance with the deeper cultural and familiar loyalty to the "old"

country. As the war dragged on beyond the late summer and fall of 1914

into 1915, tensions mounted. Inflation, increasing the price of ordinary

goods and services, along with rationing, all fanned the flames of

distrust. As time went on the war stretched into 1916. When America

finally entered the war alongside England and France in 1917,

Marshfield's German residents were forced to make some public choices.

The Marshfield Times editorialized that shortly after the war's

expansion in Europe in September 1914, that "Wisconsin, more than the

average American state is interested in the great war that is being

fought in Europe. More than a third of her population is either German

or of German extraction and thousands of Wisconsin families are

represented by relatives in the fighting army of the Kaiser." Hoping

that peace would come quickly and decisively, the Marshfield papers

backed Wilson's policy of "watchful waiting" and assured readers that

America should fear nothing except a temporary decline of exports to

Europe.

The search for reliable information regarding the war's progress and

impact, especially on the German people brought a flurry of responses

from the papers, their editorials and letters to the editor. On the one

hand, the concern surfaced that America was underprepared and could not

resist an invasion of the type that rocked Europe's borders. On the

other hand, it became the duty of people here in Marshfield to help

those suffering in Germany. Throughout late September and into October

1914, German social organizations in the city pulled together to raise

money and ship food and clothing to families and veteran's groups in

Germany. "United in bonds of common sympathy for the widows, the

orphaned children and the wounded soldiers, noted the Marshfield Times,

"members of the Marshfield Kriger-Verein and the German-American

Alliance have set out to raise a large fund for relief of the suffering

and destitute in the Fatherland which has been caused by the Great

European War." Yet this campaign was done "quietly" throughout the city

and state, surreptitiously to avoid the glare of publicity and

accusations of violating American's official stance of neutrality.

Marshfield residents benefited from the American Express's offer to ship

Christmas presents overseas free of charge, so long as the gifts were

packed and ready to ship by November 3, 1914 and were clearly marked as

"Christmas Gifts for Children of Europe."

While debate appeared on whether or not continued immigration should be

allowed during the war, the Marshfield Times in 1915 celebrated German

achievements in pharmacology, medicine, science, and its many recipients

of the Nobel Prizes. "Where is the blighting effect of Prussian

militarism?" asked an editorial rhetorically. "To the unprejudiced

observer it seems an excellent institution. Truth, justice, efficiency,

faith will win in the end, which means Germany (shall win)."

Unfortunately, this positive tone came just two weeks before the

Lusitania went down with a German torpedo which shook many Americans'

sense of security in Wilson's neutrality policy. Throughout May, 1915

the Times worked to put the best face on the sinking of the ship and

loss of American lives by blaming England for using the ship to

transport munitions under the cover of passenger service and asserting

that German submarine warfare was a logical measure of self-defense. In

the following months and throughout the summer, the paper endorsed the

neutrality policy and urged readers to avoid the war hysteria

promulgated by those in "New York" who would manipulate anti-German

sentiment to enter the war on the side of England and France.

The Marshfield Times endorsed Charles Evans Hughes for the presidency

over Wilson, because the paper assured readers that Hughes would

represent a more balanced perspective for Germany. Noting that nearly a

half million people rallied to Hughes' Milwaukee visit that fall while

only 30,000 appeared for Wilson, the paper let the impression form that

the Republican party offered a better choice than the usually endorsed

Democrats. Responding to the dissatisfaction voiced by numerous

Marshfield residents in the paper's stance, the Times defended itself

against charges of being "a spy of the Kaiser" and kowtowing to the

German Chancellor by claiming in its headline "Pretty Hard to Please

Everybody with Newspaper." Despite Wilson's close reelection in November

1916, the city celebrated Christmas with the German Theatre Company of

Bavaria giving a performance at the drama festival hosted at the Adler

Opera House.

However, after Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, relations

with the United States worsened, and it appeared that war with Germany

would become inevitable. As early as February 1917 the paper reported

that all German language columns (such as local and syndicated news

features) would disappear from the paper, because "it has been deemed

advisable for us to discontinue this feature indefinitely...." Rumors of

Wilson's death only made matters worse as an uproar swept through the

community provoked by "conflicts" between Marshfield's German and

non-German residents. Tensions mounted and were reflected in the

Marshfield Times banner reminder that "We are all Americans" and whether

or not born here, everybody should support this country as if it were

his homeland. That all was not quiet in town could be seen in the

political sniping reported in the Times as a current definition of

education making the rounds as "learning to become ashamed of father,

mother and the old home." Two days later, the United States declared war

against the German Empire.

Once a state of war existed, Marshfield residents met the new conditions

with some degree of enthusiasm. During the year and a half of American

participation in the European conflict, several distinct patterns

emerged in the newspapers. First, any public sympathy for Germany was

criticized. While not the extreme example taken in West Bend, Wisconsin,

where teaching German was forbidden in the public schools, Marshfield

readers sought to put some distance between the good or "modern Germany"

that was "orderly and industrious" and from which their family had come,

and the bad or "political Germany" that was "medieval and absolutist."

Germans who had come stateside and failed to become citizens were

chided. Asking "Can You Explain It?" the Marshfield Times denounced the

wealthy, upstanding citizens in their community or across the United

States who made money but not patriotic commitments. Further attacks

came when the paper reported the words of state senator Atlee Pomerence

who declaimed that "If your heart speaks German you are against us."

Pacifism was equated with pro-Germanism and both were denounced as

hurting the American war effort. On another occasion the Times attacked,

as traitors to the U.S., those Germans who "came here without a cent"

and who made money but did not commit by purchases of war bonds or

filing for citizenship. Even the News struck out at the Herald as

providing support for the German war effort by falsely reporting German

investments as favorable means for those looking to make money out of

the war. Each local paper did its best to assure readers of its loyalty

and faith to the American war effort.

Second, in the attempts to show support for the war effort, the city

service groups raced to raise money through the sale of war bonds during

the liberty bond drives, as well as fund-raising for the Red Cross. The

citywide goal of $14,000 was set in June 1917; the Eagles and Knights of

Columbus each tried to outdo the other in money raised for the Red Cross

and Liberty Bond Drives to show the depth of their patriotism. For those

who were slow in coming around and making a public show of support, the

News reported how one "pro-German" became a "100 percent patriot" after

being dunked in the river (which river was not mentioned) and then

forced to kiss the American flag.

Third, the increase in the cost of living created tensions that

undoubtedly helped to fuel the suspicions and animosities noted in the

first two instances. Shortages of certain basic staples had shown up at

the war's outset in August of 1914. Increases in the price of flour

showed up first, followed by sugar and then corn and animal feed. Prices

at the wholesale level doubled in a month's time as speculators did

their best to capture supplies for sales overseas. Even cigars jumped

150 percent in cost by 1917 and the price of a newspaper doubled. After

the American declaration of war in April 1917, the federal and local

governments urged people to grow their own food and preserve that

produce for home consumption; the motto "raise all you can-can all you

raise" urged citizens to keep out of the larger marketplace and thereby

reduce the pressures on climbing prices for the food needed to help feed

our own soldiers as well as our allies' troops. Soon tin cans fell into

short supply because of the drastic demand for overseas shipment and the

Times announced that cans would be provided by the local governments

only to those industrial concerns involved in packing perishable goods

absolutely necessary to the war effort. As if these aggravations were

not enough, dogs running freely through the city found their way into

these "liberty gardens" tearing up the plants and vegetables so

carefully sown. The Marshfield Times urged people to pen up, or at least

to leash their dogs (but to what effect is only speculation). Fourth and

finally, growing apprehensions that war in some form might be inevitable

brought the call for universal service to the United States for the

first time since the Civil War. Urging young men to volunteer for the

army before any draft was necessary, the Marshfield Times endorsed the

actions of young ladies of the city who played an encouraging role by

assuring "young men who failed to affiliate with the local militia

company" that they "would be stricken from their (the young ladies')

list of social acquaintances." On the other hand, the paper chided women

who married men in order to keep them out of the war. Noting an increase

in the number of marriages since the declaration of war with Germany,

the Times called for potential brides to keep a distance if they

suspected that a married man would use the excuse of breadwinner to

avoid the patriot's call to duty. The call to enlist and wear the

uniform came at precisely the same time that verbal fights over German

identity had heated up in town. War bond drives and food shortages also

had tempers flaring. Some preliminary action was seen by Company "A"

Second Regiment from Marshfield as part of the Wisconsin militia

mobilized for patrols along the Mexican and American border during the

Mexican Revolution and the famous incursions by Pancho Villa. From the

summer of 1916 through January 1917, Marshfield's young enlisted men

traveled much and fought little in this minor campaign. However, the

martial spirit dominated, and after their return and war in Europe was

begun, "A" Company formed part of the Red Arrow Division, the 32nd, from

Wisconsin that saw action in France that summer through to the Armistice

of November 11, 1918.

News of the war remained scarce until after the Armistice and then

letters from Marshfield's soldiers to their families appeared in the

Times with increasing frequency. The 32nd Division had served in some of

the bloodiest fighting from the late summer of 1918 through to the end

of the war. The soldiers of "A" Company stood up against the fierce

German offensive and allied counter attacks at St. Mihiel, Belleau Woods

and Chateau Thierry. Some returned with their health, celebrated for

their bravery, such as R. Connor who was promoted from major to

lieutenant colonel. Others came back seriously wounded, such as Leo

Luis, who lost a leg in the fight at Belleau Woods during August. He

returned home in late November to zero degree weather at three a.m. on a

30 day furlough, but welcomed nonetheless by family, friends and a small

band, to whom he showed off his artificial limb. More often than not,

the paper carried notices of those who would never come home again.

Notices in the paper included mention of funerals for Lutherans, a

memorial mass for Catholics, and the name and address of surviving

family members. "Died in France" read one column head, "Three more Blue

Stars of Boys from this Section Turned to Gold" referring to the

practice of hanging a blue star in the window of a family with a

serviceman, and a gold star for a casualty. Corporal Henry Schielz was

one native son who did not come home and who had been with Company "A"

from its initial muster and service on the Mexican border in 1916. He

died of a gunshot wound in France two days before the Armistice.

Often times there were letters from sons to families telling of the

great scenery, the "queer looking money" and the industrious farmers of

Europe. The cost of cigarettes was high, and wherever the "Sammys" went

(U.S. soldiers were named after Uncle Sam-the "G.I.s" named after the

term government issue would be another 20 years later) the natives were

glad to diddle the exchange rate from four francs to the dollar to

nearly one franc to the dollar! Underlying much of the stories that the

papers chose to print were sentiments voiced by Charles Normington who

was in Paris when the Armistice was signed who wrote, "I only hope the

soldiers who died ... are looking down upon the world today. It was a

grand thing to die for." Paul Schultz, aged 23, was one of those

Marshfield men who died for this "grand thing" and would not return to

his job at the R. J. Baker Ice Cream Company.

In February 1919 W D. Connor sponsored a banquet for nearly 400

soldiers, and sailors from Marshfield and the surrounding communities at

the armory. These most recent veterans were joined by Civil War members

of the G.A.R. and the Spanish-American war veterans. Home guards

accompanied by 20 or so young ladies dressed as Red Cross nurses did the

serving. Planning began shortly thereafter for a gala parade and

celebration for the local veterans returning sometime that summer. The

middle of June was selected as "Red Arrow Days" and the city began

fund-raising to get the needed $8,000 to carry off the day in some

style. When asked where the name "Red Arrow" came from, one returning

soldier said that it was the Red Arrow that had pierced the Hindenberg

Line, referring to notations on the military maps marking the allied

advances in the summer of 1918.

"Red Arrow Days" took place Thursday and Friday, June 18 and 19, 1919 on

Central Avenue with "a stuffed critter," parades, speeches, fireworks,

various patriotic shows and the now-celebrated Second Regiment Band from

Marshfield. The band had always been a source of local pride from its

inception at the turn of the century and its role in military service.

With the first world war, it rose to some national prominence under its

director Theodore Steinmetz (or "Steiny" as the Marshfield Times called

him) and his composition "Lafayette, We Are Here." The "stuffed critter"

turned out to be an ox for the barbecue, which weighed more than 800

pounds when dressed and more than a half ton when stuffed! The stuffing

was made of "30 pounds of bacon, 30 pounds of liver, 30 loaves of bread,

a bushel of onions and three gallons of catsup." J. P. Adler brought in

a professional cameraman to record movies of the great celebration.

Amidst it all, few may have noticed the small column head proclaiming

"Peace. Teutons Willing to Sign the Peace Terms-Day of Signing

Uncertain," with the brief explanation that the German government would

sign the peace terms unconditionally. This brief note is important for a

couple of reasons. First, those defeated were "Teutons," not Germans.

The German sympathies of three years earlier had disappeared when

enlisted men gave their lives overseas. They had become "Americans" with

little mention of their German descent; their combat as much as the home

front propaganda had served to foster a new identity of Marshfield's

largest ethnic group. Second, the unconditional surrender at Versailles

set the stage for a series of disasters, political and economic, that

would bring the world to war again within 20 years.

The war's impact could be seen in other ways as well. One obvious sign

was the great affection felt for Sergeant Willard D. Purdy who had given

his life in France. After returning from patrol in Hegenbach, Alsace, on

July 4, 1918, Sergeant Purdy was engaged in calling roll and collecting

the grenades from his men when a pin dislodged from one of the grenades.

Unable to toss the grenade away without injury to others, he ordered the

men to scatter. Smothering the grenade in his stomach, he died instantly

but saved the lives of more than a half dozen other soldiers. A year

later, the city decided to name the new junior high school and

vocational school in his honor. A second less obvious, but dramatic

impact of the war was on the population. Nearly 450 young men from

Marshfield enlisted. Approximately one in ten died in the war, either in

battle, the raging influenza epidemic, or as a result of military

service. Did the high proportion come about because such a large number

served? Did such a large number serve in order to prove their American

patriotism to a much stronger degree because they had names like Grube,

Riethus, Seidl, Schultz, Oertel, and Yaeger? Was there a need to prove

once and for all that German-Americans were not the same as "Huns" or "Teutons?"

TO THE FRONTIER

The only area in North America still available for homesteading at this

time was the Great Plains-the plateau stretching from Saskatchewan in

Canada through the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and

Kansas. In the United States before 1875, this region was better known

as the Great American Desert, a vast expanse to be suffered en route to

more promising acreage in the Far West. Frequent skirmishes with Indians

and the meager rainfall deterred most prospective farmers.

These conditions did not deter Russian Germans. Between 1872 and 1920,

nearly 120,000 ethnic Germans emigrated to America from homes on the

Russian steppes-flat, dry terrain that resembled the prairies of the

Dakotas. Their ancestors had been lured to Russia by the promises of

rulers Catherine the Great (reigned 1762-96) and Alexander I (1801-25),

who wanted German farmers to cultivate the untitled steppes, and, later,

according to her invitation, to "serve as models for agricultural

occupations and handicrafts." Among the incentives were promises of

religious liberty, exemption from military duty, cash grants, and

self-government. There were 300 colonies of German settlers in southern

Russia, scattered along the lower Volga River and in the Black Sea

district, when in 1870 the czarist government began to revoke their

original privileges.

The inhabitants of these colonies lived a life separate from their

Russian neighbors and closely tied to their church, a pattern they

duplicated in North America in independent communities of Lutheran,

Catholic, or Mennonite persuasion. Most of those who chose the United

States as their home (many Mennonites went to Canada because it granted

them exemption from the draft), settled between the Missouri and

Mississippi rivers to the east and the Rocky Mountains to the west. The

isolation of Russian Germans in this area naturally slowed their

assimilation into American society, but their success in farming the

inhospitable land was key to the development of the Great Plains as the

"granary of the world." By 1920, 420,000 of them lived in America,

spread across most of the United States and in the western provinces of

Canada. Russian Germans, who had introduced a variety of grain called

red hard winter wheat from Turkey to the Volga River region, then grew

the crop on their farms in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado.

In so doing, they helped make the United States self-sufficient in food

production to this day.

URBAN TENSIONS

Not everyone who arrived in the 1880s met with such opportunity. In the

city as well as in the countryside, the average German immigrant found

fewer acres and less work than had greeted his predecessors.

Industrialization was altering life in American cities much as it was in

Germany. Artisans such as bakers, furniture workers, and toolmakers

found their age-old skills of little value-factory work required the

speedy completion of one small task, not a craftsman's painstaking care.

A 12-year-old boy who had to learn the meticulous skills of

cabinetmaking, for instance, might now stand for years at a machine

repeatedly making one small item.

This trend led to high unemployment and to living conditions that were

often miserable. In 1884, one German cigar maker in Chicago could find

only occasional work; his family of eight lived in a three-room house

that was "scantily and poorly furnished, no carpets, and the furniture

being of the cheapest kind." His children were sick "at all times. "

Workers who found permanent employment could take little pride in their

work and were often "exploited. A conductor who put in a 16-hour day

protested that "the company is grinding [me] and all the others down to

the starvation point."

Nor did city officials make the workers' plight any easier. During the

last decades of the 19th century, Chicago was the scene of repeated

police abuse and election fraud. Meetings organized by workers were

often disrupted by police, and police harassment and violence were used

to get striking workers back on the job. The German newspapers of the

day reported many cases in which politicians moved voting places

overnight to prevent workers from voting in the morning, closed them

before the workday ended, intimidated those who did arrive, and stuffed

ballot boxes with illegal votes. The German-language newspaper Verbote

responded indignantly to a blatant case of vote fraud in 1880: "We are

fully justified in saying that the holiest institution of the American

people, the right to vote, has been desecrated and become a miserable

farce and a lie."

These disillusioning events, coupled with poor living and working

conditions, encouraged German immigrants to turn to labor unions as

organizations that could best represent their interests. In 1886, almost

one-third of the total union membership in Chicago was German, and of

all the ethnic groups, Germans contributed the most members. In fact,

more Germans joined labor unions in that city than did native-born

Americans.

German involvement in the labor movement did not sit well with nativists,

who, in the last decades of the 19th century, were again seeking support

for anti-immigration laws. With the railroad strike of 1877 and the

Haymarket Riot of May 4, 1886 (which broke out when someone at a

workers' protest threw a bomb at policemen, who fired randomly in

response), nativists claimed that German immigrants-with their

predilection for socialism and radical labor activism-had imported the

trouble. Though it was never determined who threw the bomb, eight men

were tried in the wake of the Haymarket Riot; four were subsequently

hanged, three of them German-born. This fact fueled the nativists' fire,

as did the surge in German (and other) immigration in the 1880's.

UNITED GERMANY: INSPIRATION AND THREAT

The unification of Germany by the Prussian prime minister Otto von

Bismarck in 1871 focused American attention abroad long before World War

I broke out in 1914. Some Germans in the United States were

unenthusiastic: German-American Catholics in particular grew bitter at

the oppressive measures the "Iron Chancellor" used to achieve his ends,

and many emigrants now left the German empire in order to avoid being

drafted into the Prussian army. But other German Americans overlooked

Bismarck's failings, which they felt were exaggerated by the

English-language press, and emphasized instead his leadership in the

defeat of the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and the

creation of a united Germany.

In fact, to an outspoken minority of German Americans, the event was an

inspiration. If Germany could be united, they reasoned, why could not

the diverse groups of Germans in America-never before united

politically, but sharing a language, and to a large extent, a

culture-act as a potent and unified bloc? A speaker in Cincinnati leader

expressed this viewpoint by urging his compatriots to "make an end to

all our petty quarrels.... Let us make our power felt, and let us use it

wisely."

By the 1890s, this sentiment became more popular and was echoed in many

of the 800 German-language publications across America, which shifted

the focus of their news away from America and back to the fatherland. In

part, this nationalism was in response to a sharp drop in German

immigration at the end of the 19th century. This led to fears among some

German Americans that without strong efforts to promote German culture

their communities would assimilate completely, and the German language

as well as German art, music, and literature would no longer have a

presence in the United States. Promoting German culture did not mean

abandoning the new homeland; indeed, many German Americans believed that

the national interests of Germany and the United States were

complementary, so that support for the one would ultimately benefit the

other.

Native-born Americans grew increasingly wary of this German political

and cultural activity in their midst. Nativist groups such as the

Immigration Restriction League and the American Protective Association

sought to limit immigration and supported measures-the prohibition of

alcohol, woman suffrage (most suffragettes advocated prohibition),

Legislation requiring all students to speak English-that German

Americans opposed.

German Americans responded by forming their own organizations, most

notably the German-American National Alliance, founded in 1907 by an

American-born engineer from Philadelphia named Charles J. Hexamer.

Nativists, though, heard in the Alliance an echo of Germany's own

Pan-German League, part of whose platform was "to oppose the united

commercial power of our enemies, the Anglo-Saxons." Could Germany be

trying to establish a power base in the Western Hemisphere, using German

Americans as an advance guard?

Suspicions were fed by American fears of Germany's leader Kaiser

Wilhelm, who had come to power in 1890 and whose militarism led many to

believe he was bent on world domination. To a growing number of

Americans, German-American unity seemed an expression of support for the

Kaiser's imperialistic path, or at least a sign Of split loyalties. As

early as 1894, in a speech entitled "What 'Americanism' Means," future

president Theodore Roosevelt denounced immigrants who regarded

themselves as "Irish-Americans" or "German Americans." In his view, they

were distinctly unpatriotic: "Some Americans need hyphens in their names

because only part of them has come over. But when the whole man has come

over, heart and thought and all, the hyphen drops of its own weight out

of his name."

The term hyphenate became an increasingly popular insult to describe

just about anybody who felt strongly about his ethnic identity. Ethnic

tensions in America increased in August 1914 when fighting broke out in

Europe. President Woodrow Wilson initially set the nation on a course of

neutrality, urging that Americans be "impartial in thought as well as in

action ... neutral in fact as well as in name." But before the war was

one month old, reports of German atrocities in Belgium (especially the

burning of Louvain, with its ancient library) shocked many Americans and

emboldened the American caricature of the goose-stepping, brutal Hun.

Life magazine published a cartoon in late July 1915 that fueled this

stereotype: a German officer with pointed helmet struts across the page;

suspended from his bloody bayonet are an old man, a woman, and two small

children. German submarines prowled the Atlantic, and by the time one

sank the British passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915, killing 1,200

persons (including 124 American citizens), Wilson was hard put to

recommend neutrality in thought or deed.

The vocal leadership of the German-American community inadvertently

worsened tensions. The depredations of Belgium, they believed, had been

exaggerated by Germany's enemies, especially Great Britain, in a

deliberate attempt to draw the United States into the war-an attempt

made all the easier by the two nations' common language and Wilson's

noted allegiance to English culture. The publisher of the

German-language Omaha Tribüne, Val Peter, reflected this mentality in a

1915 address to the Nebraska branch of the German-American National

Alliance:

Both here and abroad, the enemy is the same! perfidious Albion

[England]! Over there England has pressed the sword into the hands of

almost all the peoples of Europe against Germany. In this country it has

a servile press at its command, which uses every foul means to slander

everything German and to poison the public mind.

But by dismissing every reported atrocity as anti German propaganda and

portraying the nation's leadership (especially President Wilson) as

unsuspecting dupes of the British, prominent German Americans came

across to the American public as callous, uncaring, and undiscriminating

in their support of Germany. For example, although most German-American

newspapers and organizations expressed dismay over the lives that had

been lost when the Lusitania was torpedoed, they also made excuses for

the German action: United States citizens had been warned by the German

embassy about traveling on British ships; Germany was forced into

submarine warfare by the British blockade of Germany; Congress should

have ensured a policy of strict neutrality by forbidding the sale of

American weapons to the British. These excuses rang hollow to many

Americans who were distraught over the tragic loss of life.

President Wilson vigorously repaid the attacks on him in the

German-American press with a number of speeches made in the fall of

1915. In his State of the Union address to Congress that year, Wilson

condemned "citizens of the United States, . . . who have poured the

poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who

have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into

contempt." With language that was more characteristic of the fiery

Roosevelt, Wilson went on to insist that all such traitors must be

crushed out," and that "the hand of our power should close over them at

once." Wilson's speeches, implicitly equating support of Germany with

treasonous anti-Americanism, marked the beginning of the end of American

neutrality.

The United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, with this

declaration by President Wilson: "The world must be made safe for

democracy ... the right is more precious than peace." He had been driven

to declare war, he told Congress, by Germany's continuation of submarine

warfare. But there was another major factor in Wilson's decision. A

telegram, written by German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann and sent

to Mexico, had been intercepted by the British navy. In the telegram

Germany offered to help Mexico regain Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, a

plan evidently designed to keep U.S. troops out of Germany's backyard by

keeping them busy at home. The telegram convinced both Wilson and the

American public of Germany's hostile intentions toward the United

States. Unfortunately, like many of Germany's actions during World War

1, it sparked hatred of all things German. As American soldiers - many

of German descent - arrived on the battlefields of Europe, anti-German

hysteria welled up in cities, towns, and rural outposts across America.

ANTI-GERMANISM GROWS VIOLENT

On the night of April 4, 1918, a year after the United States had

declared war against Germany, a group of Maryville, Illinois, coal

miners apprehended Robert Paul Prager, a co-worker whom they suspected

of being a German spy. They marched him from his home in Collinsville,

forced him to kiss the American flag and to sing patriotic songs in

front of a gathering crowd, and questioned him about his activities as a

German spy. Prager insisted on his innocence and on his loyalty to the

United States. But the mob was not appeased, and they hanged him from a

tree on the outskirts of town.

Prager's death was the culmination of a year of harassment of German

Americans. Theodore Ladenburger, a German Jew living in New York, wrote

that "from the moment that the United States had declared war on

Germany," he was made to feel like "a traitor to [his] adopted country."

Moreover, he continued: ... in view of my record as a citizen I did

expect from my neighbors and fellow citizens a fair estimate and

appreciation of my honesty and trustworthiness. It had all vanished.

Outstanding was the only fact, of which I was never ashamed-nor did I

ever make a secret of it-that I had been born in Germany.

German Americans were intimidated into buying Liberty Bonds (sold by the

U.S. Treasury to finance the war), imprisoned for making "disloyal"

remarks, and forced to participate in flag-kissing ceremonies like the

one that preceded Prager's lynching. Citizens from Florida to California

were publicly flogged or tarred and feathered. Homes and schools were

vandalized. Mennonites, who firmly opposed all wars, were especially

persecuted; in 1917-18, more than 1,500 Mennonites fled the United

States to settle in Canada.

Hysteria also threatened German cultural institutions. Attacks on German

music included the banning of Beethoven in Pittsburgh and the arrest of

Dr. Karl Muck, the German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony, on

charges that he was a threat to the safety of the country. The same

motive lay behind the removal or vandalism of statues of poets Johann

Goethe and Friedrich Schiller and other German cultural giants.

German-language classes were dropped from school curricula and German

textbooks banned. Under a 1917 law, German-language newspapers had to

supply English-language translations that were reviewed for approval by

local postmasters. If the material was found to be unacceptable, mailing

privileges were withdrawn.

Perhaps the most ridiculous example of the rush to "de-Germanize"

America was the removal, in 1917, of the figure of the goddess Germania